November 19, 2019

KING BABY SYNDROME

ON TOUR WITH SAUL ADAMCZEWSKI & HIS INSECURE MEN

Like an old travelling band, Insecure Men brought their suits on coat hangers. Although with my Satanic priest outfit that I will wear to introduce the band each night, I am the only one, besides Saul and his corpse pallor, with anything that resembles a Halloween costume.

We stand outside Dropout Studios at midday in November 2018 for the thousand-mile round trip that ends at the 900 capacity Queen Elizabeth Hall in London. “Where’s Saul?” asks Aidan Clough, the youngest of three keyboard players, pale faced, dressed in a mackintosh and military beret.

Since Insecure Men is essentially Saul’s band, he’s allowed to do pretty much whatever he likes, and tour manager Jonny Ray’s schedule has to adjust to his movements, which all members of the touring party accept as part of the job. Because in the eight years I’ve known him, Saul has never had access to a proper bank account; he has rarely, for brief periods of time, owned a phone; on foreign trips he requires his passport be carried by a designated adult; he frequently turns up to his own shows without a guitar; and at the time of writing, as is standard, he does not have a permanent abode.

The bus stops outside a big white Georgian house in Notting Hill with a ladder outside for grotty rockers to climb. Jonny Ray knocks on the door. To our surprise, Saul emerges not down the social ladder, but out of the front door. He’s wearing a shirt and tie, a smelly fur hat, and a pair of Primark sports sunglasses with neon pink hinges. He’s been up all night with the saxophone player Alex White, who goes straight to the back seat, lies down and falls asleep. Unlike their last trip around Great Britain, there’s no mezzanine bed on this trip, so Saul stays downstairs in coach class, too jittery to read his Jonathan Meades book, and eases back into one of his many social compartments by slagging off his companions from the previous night.

Bladders emptied onto mansion walls, all Insecure Men are in the Volkswagen minibus on the way to Birmingham, browsing through the books and magazines I brought along to promote misanthropic ideas and cause tension, since they all have girlfriends and they keep insisting, “there’s no sex in this band.”

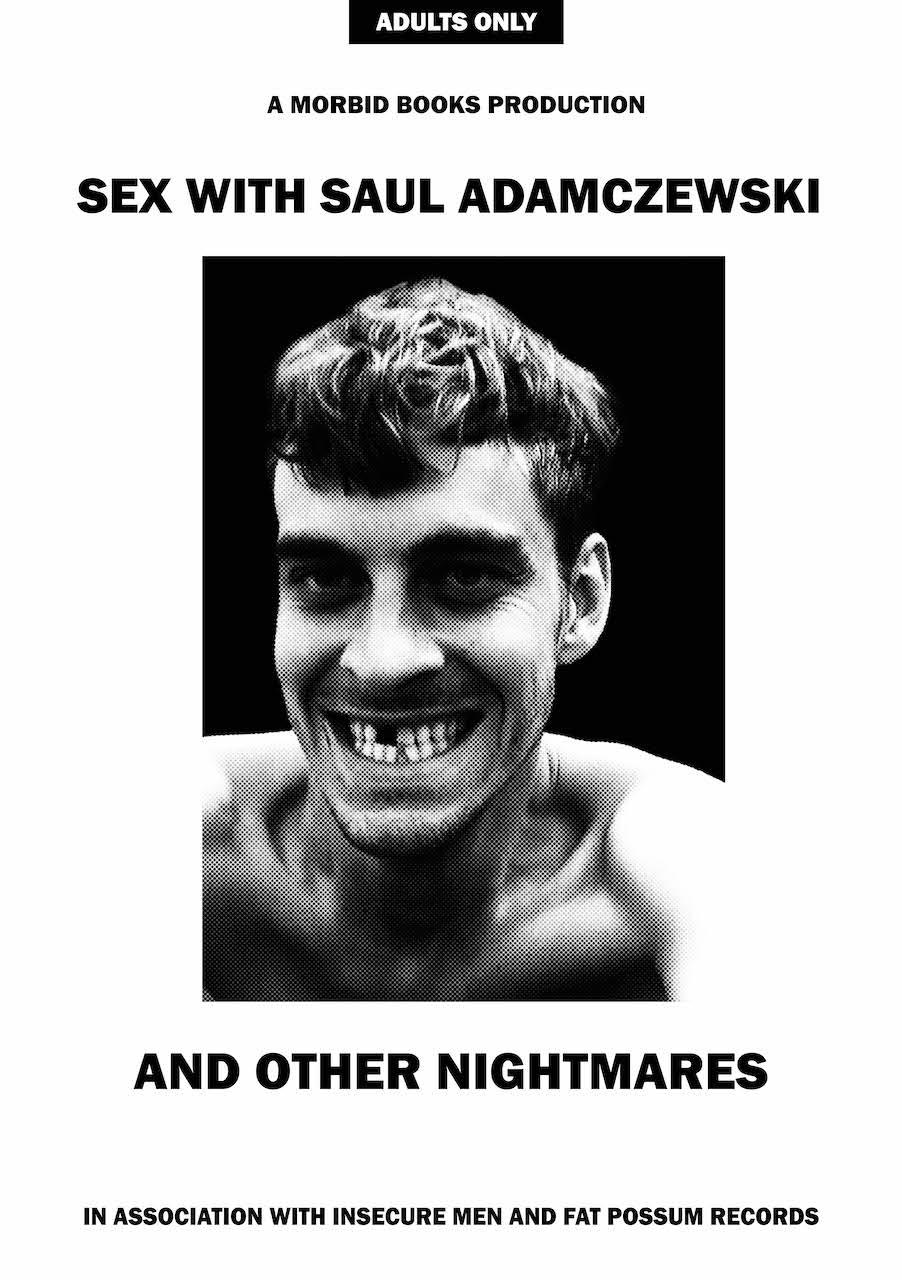

In addition to the “tour programme” I wrote, Sex with Saul Adamczewski & Other Nightmares, I brought along some copies of The Satanic Bible, 120 Days of Sodom, Girlvert: A Porno Memoir, Takeaway by Tommy Hazard, and a brown paper bag full of sticky, second-hand copies of vintage porn titles including Men Only, Experience: the magazine written by women, a 1970s Guide to Sexy London, and New Cunts, vol. 76.

“Hairy arses,” Joe Isherwood shouts a mile down the road, holding open a copy of Men Only. “Look at these hairy arses.”

I let everybody know from the outset that despite being the stage announcer, I haven’t prepared anything to say. “I think you should announce that Jools Holland has died,” Saul says. “Trick or treat!” We eventually settle on one of my poems, “Death."

We stop for lunch at a service station. “We’re going to get some funny looks in here,” Saul says. Not before we have a photo taken in front of the concrete control tower with the yellow and blue Insecure Men scarves held aloft, the backdrop already calibrated in his unconventionally strategic mind for its impact on social media.

Social media promotion is the part of the job of professional musician that I was initially surprised to see Saul participate in, let alone exceed at, and not only because it requires access to an electronic communication device. But the better you understand what motivates him, the easier it is to find coherence in the contradictory phenomenon of Saul Adamczewski as a social media personality.

By appearing in a variety of wacky guises that frequently reference extreme ideologies, starting with Communism around the time of the early Fat Whites, then graduating onto Nazis for the Whitest Boy on the Beach phase, then North Korea for Insecure Men, Saul has made himself into a kind of nihilist stunt boy, an emaciated carnival grotesque who explores the attention-grabbing, comedic potential of horrible ideas. At the end of the day, Saul doesn’t really care if most people love him or hate him, as long as enough of them are paying attention to him, as he grins at them through the window of his gap tooth.

In Birmingham, once the equipment is loaded out of the van and the soundcheck is done, there’s not a lot to do besides change outfits, sing karaoke and drink. The only mysteries for a travelling band are in trivial details such as the size of the backstage green room and contents of the rider—usually about twenty cans of beer, a bottle of spirit, some Coca-Cola and cold snacks. The band seem to be developing a robust dependency on canned lager.

“That sounded good,” Jonny Ray says of the sax-heavy sound.

“It sounded like shit,” Saul says, “but the sound man looked so stressed, I didn’t want to say anything.”

With each man's daily £10 dinner money or "per diems" handed out, we decamp to the Old Crown pub. Marley and Ben are the only ones to order food with it. “I like the colour of this speed,” Saul says, tapping and glaring at the bag. It’s yellow, the colour of Mark E. Smith’s stash, and destined to touch many nostrils in the next seven days.

Looking increasingly uneasy with not being the centre of attention, Saul tells us how he overcame his fear of flying. A few years ago, before a tour to Japan, his management sent him on a course for aerophobes at Heathrow airport. They were taken on a short flight while experienced pilots held their hands and talked reassuringly to them. “I got a special certificate and everything,” he says, emphasising the “special.”

As the show gets nearer, he straps on a guitar and walks around backstage. “I wrote this one for Neil Young,” he says of a track called “Brown Summer.” The subject matter is obvious but the melody is sweet.

At times like this, Saul comes across as the kind of showbiz veteran I often forget he is, in the alternative reality we inhabit. “You’re on the Insecure Men tour, so by definition you are a failure,” he says. “Nothing can go wrong from here.”

///

One of the younger men said speed is his new favourite drug. This morning he’s not slept, having stayed all night in front of the silent television screen. I meet them at 11am in the lobby of the empty hotel, whose ambiance seems to board the bus, ghostlike. We’re on the way to Manchester, listening to music to use as a backing track to my new intro. The music from The Shining plays, and the matter is agreed. “Hail satan.”

“I love touring with this band. It’s so placid.” When I ask him why he has three keyboard players, he says he doesn’t need them all but couldn’t fire them.

After the gig, the men went back to their leader’s hotel room and drank a few more beers before bed. No sex, no more drugs. Saul emerged in the morning wearing a pair of brown suede moccasin slippers and red tracksuit bottoms. Despite founding another one of his joke movements, Musicians Against Touring, he seems as settled and comfortable on the bus as anywhere else. Despite being the same Animal-style madman, a dust cloud of clatter and noise, a raving lunatic with a cigarette and bad opinions, Saul is the best person I have known him to be in the confines of the Volkswagen minibus, a sort of friendly, mobile therapy centre, where he is driven around in relative comfort, stopping whenever he needs a shit, surrounded by the soothing influences of his bandmates. The opposite of the antagonistic thieves’ den of the Fat White Family, this band, crucially, does not deflect Saul’s negative emotions back at him.

I, on the other hand, have no obligations to Saul. I can come and go from the tour as I please, and since I am here largely for the purposes of entertainment—my own and theirs—I am more inclined to disrupt the equilibrium by introducing subversive elements into the mix. As the person who introduced him to the magic of the Manson Family Jams album, and having dropped other ideas into his head over the years, I am aware that Saul is highly suggestible. As a musician and social media personality (ho, ho!), he attains his status by reworking arcane and unfashionable cultural approaches into new sounds, images and slogans that have found a dedicated following among a small tribe of nihilistic millennials.

On the way to Manchester, Saul grabs my copy of The Gates of Janus: Serial Killing and its Analysis by the Moors Murderer, Ian Brady. He spends the journey to Manchester sprawled across two seats with his hand down his jogging pants, transfixed by the book.

Given how we’re on our way to Manchester, where Brady kidnapped his victims, I’m undecided whether I should add him to the list of people who lived a full life—from Sylvia Plath to Adolf Hitler—in my introductory poetry reading. Jonny Ray says it would be suicidal, I would get glassed. Saul taps me and shakes his head, grinning. “Do it.”

The band are in a rush over to the BBC when the bus packs up on them. They ran the battery down playing I Need Drugs by Necro at full blast while the vehicle was stationary, and can’t get it to start. Cabs are out of the question, so eight Insecure Men spend twenty minutes pushing it up the hill and out of the parking bay while at the same time jumping in the side door before it stops. The tableau resembles Wacky Races—Dick Dastardly and Mutley and the Anthill Mob with synthesisers.

They arrive back at the venue while the support band is playing. A local friend and madcap personality arrives backstage wearing a Grace Kelly-style funeral dress and veil. She necks ecstasy on the roof terrace and assists me handing out tour programmes to the audience. A northern lad who seem distantly related to Mark E. Smith asks me what it is.

“A programme.”

“What’s a programme?”

“You know when you go to the football or the theatre, they sell programmes?”

He glares. “I don’t go to the football or the theatre.”

“It’s free, just take it.”

“No thanks.”

A minute later, the same lad comes up to me. “I’ve just seen somebody else’s. It’s short stories, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” I say.

“Why do you say programme, then, not short stories?”

“It’s a programme with short stories in it. Do you want one?”

“Go on then.”

“Thanks.” Two minutes later: “Actually, you can have it back.”

The room is so full we can’t get to the people crowded at the front, so Miss B. goes onstage, surreally beautiful with eyes popping out from behind her funeral veil, and starts offering them to anyone who feels sexy, anyone who looks sexy, anyone willing to get their tits out. They grab for them and gobble them up like geese with bread.

After the show, fifteen people are crowded into a dressing room the size of a janitorial cupboard. The venue promoter comes in and tells us to stop smoking. “Why?” Saul asks.

“It’s illegal, you’ll get fined.”

“How much?”

“Five hundred quid,” the promoter says, with an air of hollow bravery.

“OK, I’ll pay it, now leave us alone.”

At the end of the night he has to be dragged out of the dressing room to prevent him from knocking over the pint of his own piss he left balanced on the radiator.

We’re supposed to go to some kind of after-party, but Saul doesn’t want the whole band there. “The elite only,” he tells one of them on the phone.

In the back of the cab, he continues to drunkenly explain his behaviour towards other people. His therapist, who he talks to every week, says he has King Baby Syndrome. But Saul doesn’t respond to criticism like most people would. What you or I might find humbling or deflating, Saul embraces as validation.

“The thing is, by calling it King Baby, he’s actually making it seem attractive,” Saul says. “Because you’ve got two very positive words, King and Baby. You put them together, and it becomes even more positive.

“I have no money,” he says, getting out of the cab, emptying his pockets, leaving us to pay for the ride. “I know Matt Johnson from Fat Possum is stealing from me. I like that. The accountant is stealing from me too, but I don’t care.”

Sprawled across the floor at the afterparty, Saul tells an offensive and distorted account of his family's experiences of World War II which will later get both of us into trouble with his father, and how he owns a small patch of land. In addition to a bottle of vodka, ketamine and some “cocaine,” the thing that really keeps him going all night is music. He listens to pedal-steel country music, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, and the Ulster Volunteer Force’s version of I Will Survive at least three times. He dances around the living room and sings along to the refrain, “Fuck the Pope and the IRA.”

While all this is going on, apparition of our friends—or in some cases, enemies—appear in Saul’s mobile justice centre. He takes great amusement in pointing out their faults, frailties and defects. “Do you have any morals?” he asks me, before thinking. “Wait, I know despite what you say, you do. I genuinely don’t!”

He crashes out around 8 a.m., when he’s finally run out of music to play on the laptop and has resorted to watching Isis beheading videos.

///

On the outskirts of Glasgow, we stop at a mechanical workshop on the edge of an industrial waste dump to get the van repaired. Giant mounds of discarded metal radiate strangely, like temples in the mist. “Let’s get a photo in front of that pile of shit,” Saul says.

“Which pile of shit?”

“The big red one.”

As the band traipse across the wasteland, a car comes through the gate. A Scotsman asks what we’re doing, what’s our business? It’s hard to explain. Neither side can understand the other. We don’t get why he’s protective of his mountain of waste, and he can’t comprehend our aesthetic attraction to it.

After any length of time, a tour bus becomes a kind of micro state with its own rules, hierarchy and culture, and interactions with civilians on the other side of the glass become increasingly difficult, unwanted experiences. This is especially true of Saul’s band, where the citizens quickly learn to inhabit the King Baby’s warped version of reality. At a service station earlier, he came across a couple of gentle old ladies selling remembrance poppies. He bought a poppy on a cross, turned it upside down and used my sharpie to colour it black. For five minutes, he decorated that piece of wood with the nib of the pen like nothing else in the world existed.

He’s already thinking about Instagramming his cross and a giant “Hail Satan” poppy. I wonder if he’s ever been offered product placement on his popular social media pages. “Only Morbid Books,” he says. “I’m doing good as your brand ambassador, aren’t I?”

“Yes, you are,” I assure him sincerely.

“But you don’t pay me.”

“No, but you do benefit from your association with the literary avant-garde.”

“I do,” he smiles. “It’s a good Satanic alliance.”

A little further down the road, Saul turns around from the front seat and points to the Ian Brady book. “I’ve got a question,” he says. “Do you think, if I took this book to therapy and quoted it, they would lock me up?”

“No,” I say.

“Good,” he smiles, very satisfied. “Because I’m really into this Brady philosophy that you should just do whatever feels good for yourself. He’s constructed a watertight argument. It’s amazing.”

As gratifying as it is to see my ideas and words being repeated, I start to feel guilty for pumping antisocial concepts into his head, for the negative effect they have on the others. His childhood friend, bass player and fellow songwriter Ben Romans Hopcraft, who is an exceedingly tolerant person, said that he wasn’t happy with Saul’s elitist behaviour last night, when he refused to invite some of the band to the party. Earlier this morning, Saul was a totally obnoxious cunt to Jonny Ray on the phone, ordering him to take a detour to pick him up from the party, and buy him a bacon sandwich on the way over. This kind of behaviour is certainly not a surprise to me, having witnessed way worse in eight years, but it’s the first time I feel like my influence is having a negative effect, besides maybe the time I almost convinced him to burn down the Windmill in Brixton as a protest against the Royal wedding.

///

By the time we reach Glasgow, Satanic indulgence has taken its toll. The show is in the calm, sophisticated arena of the Centre for Contemporary Art. A lush vegan meal provided by the promoters adds to the serenity of the atmosphere like a tranquiliser.

Backstage, I try to explain to the band that they should wait until the end of my reading before they walk onstage. Because in Manchester, a couple of them strolled on just as I was hitting the high note, and the audience cheered a few seconds too early. It’s not a hard skill to master, waiting until you hear the words “Death is a form of grace, a kind of mercy,” before you walk, but from the looks in their eyes, I can tell that it will be down to chance when they decide to move their limbs in conjunction with their minds.

The audience cheers for Dale Barclay’s name added to the list of people who truly lived, and therefore truly died. But the band walk onstage even earlier this time, about halfway through, so I have to skip ahead to the last four lines—not ideal, as its effect is achieved through momentum, and the accumulation of meaning. Nonetheless, Jonny Ray tells me the Uri Geller line is hitting the sweet spot.

After two stonking performances in Birmingham and Manchester, the Glasgow show is merely competent. “It was fine,” Saul says, fully aware of the sedated mood. “I loved your intro, though, adding Dale to the list of greats.”

Not long ago, around the making of the second Fat Whites album, I thought Saul would soon be adding himself to the list of people I read out who have truly lived, and therefore truly died. While still careering towards the abyss, in recent time he seems to at least have taken his foot off the gas. “Are you partying tonight?” I ask.

“No chance, brother. I’ve got diarrhea.”

“Oh…”

“Are you leaving us until Brighton?”

“I’m afraid so.”

“We’re going to miss you.”

“I’m going to miss you too,” I say. “Why are you doing coke?”

“It gets me home.”

///

On the way to Brighton, I receive a message from Saul. “You missed a great van drive after Glasgow, brother!” I later learn the band spent their day off in Bradford at an all-you-can-eat Indian restaurant, then drinking beer and farting in their Travelodge. In addition to the explosions coming out of their arses, after a bad show in Leeds, somebody bought a load of fire crackers and set them off in the van. Aidan sends me photos of Saul swinging upside down like a chimp. “Things got pretty dark once the Satanist left the tour,” Jonny Ray says.

I rejoin in Brighton on the night of the Lewes bonfire, a pagan carnival that has cleared the streets and the venue, The Haunt. The band are now so morose, they can barely talk. We spend what seems like hours drifting from backstage cubby hole to sea front to the front doors of pubs before turning back, unable to afford a drink. Tom, who lives in Brighton, shows us the alley where Phil Daniels had a quickie with Leslie Ash in Quadrophenia. Even our attempts at giving each other oral sex on the sea front are a miserable failure. When the lights come on, the spiritual darkness is temporarily lifted as the band put in a flawless performance. Deep down, the darkness still lingers. On the drive home, to the soundtrack of Frank Sinatra, I get drunk for the first time in months.

///

I wake on the morning of the Queen Elizabeth Hall show thankful my contribution doesn’t require me to feign happiness. For weeks, I have been liaising with Saul’s manager, Mat, about the setup for this event, which requires every element to be preapproved by the state-owned venue’s bureaucracy, from the bands on the bill to the items sold on the merch stand. And I was always pleasantly surprised to hear, after every correspondence, that the venue had not yet objected to us putting the Sex with Saul booklet on every seat. So we paid for 900 of them to be printed and kept quiet in the hope they wouldn’t notice that we would be distributing extreme pornographic material at a fourteen-plus show.

Well, they did notice. On the day of the show, somebody in the production office asked to see this programme. So I went to see the censors in their office, and to their credit, they were all having a good laugh at it, but they said they could not allow us to distribute it in the auditorium.

The disappointment of having our masterplan foiled is soothed by the luxuries of the backstage area, a soft furnished underground labyrinth of comfort. There are grand pianos to play around on, an infinite supply of food and drink, and cafetieres filled with strange opiated mixtures.

“I fell off the wagon,” Saul says. “I would be too nervous otherwise. Do you like my hat?” It’s a woolly Scottish bobble hat that used to belong to the poet Jock Scott.

Other narcotics make their way around. Jonny Ray keeps trying to hide the beer refills to keep the band from fucking up like they did in Leeds.

Stewart Home arrives at 6.30 p.m. and manspreads on the sofa. I was nervous about introducing the novelist and self-proclaimed antifascist to Saul, but they seem to get along just fine, talking about obscure punk bands. He is due to give a reading in the lobby, but the authorities censor his recreation of Defiant Pose, the novel that culminates in two anarchists having sex on a boat as the House of Commons is set on fire. He spends fifteen minutes feeding one of his books into a shredder as I hand out programmes.

The crowd includes a few friends and many familiar faces who I try to avoid. Saul’s stepmother firmly declines a booklet, but his sister takes one with seditious glee. Ten minutes before stage time, a South Bank Centre enforcer asks me what I’m doing. “This is not the designated point we agreed!” he stresses. He’s referring to an agreement that the programmes should be handed out by the merch stand, which is five metres away. But it doesn’t matter. The damage is done. We gather in the dressing room for a drink and a hug. “Do not walk until you hear the words, Death is a form of grace, a kind of mercy,” I say.

“Nobody moves until I move,” Ben says.

“Okay,” Saul says. “By the way, I liked what you said in Birmingham. Can you say that again?”

“What did I say in Birmingham?”

“You said something about me not needing a Halloween costume. It was funny. I liked that.”

“But it’s not Halloween,” I say. “It wouldn’t make sense today.”

“No. But you said my name, Saul. Can you say that again? Can you make it about me?”

The lights go down and I am reminded of another poem, not by me. Perhaps I should have read this instead:

The murmurs ebb; onto the stage I enter.

I am trying, standing in the door,

To discover in the distant echoes

What the coming years may hold in store.

The nocturnal darkness with a thousand

Binoculars is focused onto me.

Take away this cup, O Abba, Father,

Everything is possible to thee.

I am fond of this thy stubborn project,

And to play my part I am content.

But another drama is in progress,

And, this once, O let me be exempt.

But the plan of action is determined,

And the end irrevocably sealed.

I am alone; all round me drowns in falsehood:

Life is not a walk across a field.

‘Hamlet’—Boris Pasternak

An alternative version of this "youth team report" appears in the Fat White Family’s 2019 tour programme

Lev Parker